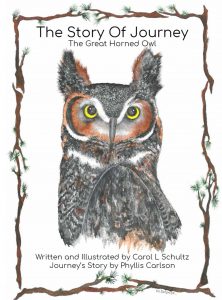

The Story of Journey: The Great Horned Owl — Behind the Book

I’m Carol L. Schultz, and I had the pleasure of talking about my children’s book The Story of Journey: The Great Horned Owl on the UP Notable Book Club presented by the Upper Peninsula Publishers & Authors Association (UPPAA) and the Crystal Falls District Community Library. In this post I’ll share how Journey’s story began, why I chose to write and illustrate it, some of the most memorable moments from Journey’s life, and a handful of fascinating facts about great horned owls that I included in the book.

I’m Carol L. Schultz, and I had the pleasure of talking about my children’s book The Story of Journey: The Great Horned Owl on the UP Notable Book Club presented by the Upper Peninsula Publishers & Authors Association (UPPAA) and the Crystal Falls District Community Library. In this post I’ll share how Journey’s story began, why I chose to write and illustrate it, some of the most memorable moments from Journey’s life, and a handful of fascinating facts about great horned owls that I included in the book.

About me — why I write and paint

I grew up in the Upper Peninsula as the middle child in a lively family of six. Nature—and the U.P.’s forests, lakes, and wildlife—has always been my inspiration. After raising my family and working outside the home, retirement gave me time to do what I love: paint and create children’s books. I’m a self-taught artist who favors watercolor (with some ink for detail), and I enjoy telling nature-inspired stories that encourage kids and adults to appreciate the world around us.

How Journey’s book came to be

My connection with Journey began through Phyllis Carlson, a longtime wildlife rehabilitator who cared for him. I had seen her programs and read about Journey’s retirement in a local paper. I asked Phyllis if she’d be interested in a children’s book about Journey. She said she would—she just didn’t know how to get started. I’d been learning to self-publish, and because I wanted to use my own illustrations and keep control of the artwork, self-publishing made sense.

My connection with Journey began through Phyllis Carlson, a longtime wildlife rehabilitator who cared for him. I had seen her programs and read about Journey’s retirement in a local paper. I asked Phyllis if she’d be interested in a children’s book about Journey. She said she would—she just didn’t know how to get started. I’d been learning to self-publish, and because I wanted to use my own illustrations and keep control of the artwork, self-publishing made sense.

Phyllis and I met several times. She told stories, I took notes, and I did my research on great horned owls. When the manuscript and illustrations were nearly finished, we spread everything out across my kitchen counter and dining room table and went page by page together, making a few adjustments. After editing and working with my printer, the book was ready.

Journey’s story — a concise retelling

Journey was born in a 100-year-old pine tree in Quinnesec Cemetery (Dickinson County, Michigan) during the winter of 2000–2001. Great horned owls often start nesting in winter and use old nests, hollows, or structures instead of building new ones. Journey was one of two eggs; after an incubation of about 30–37 days, the owlets hatched covered in soft down that later turned to brown feathers. By early June the youngsters were flying, and by July they were roughly four months old and hunting on their own.

Journey was born in a 100-year-old pine tree in Quinnesec Cemetery (Dickinson County, Michigan) during the winter of 2000–2001. Great horned owls often start nesting in winter and use old nests, hollows, or structures instead of building new ones. Journey was one of two eggs; after an incubation of about 30–37 days, the owlets hatched covered in soft down that later turned to brown feathers. By early June the youngsters were flying, and by July they were roughly four months old and hunting on their own.

One day, while hunting a mouse across the road, Journey was accidentally struck by a car and badly injured. A passerby named Steve found him and contacted Phyllis. With the proper permits and experience caring for wildlife, Phyllis took Journey to a veterinarian who determined his wing could not be fully repaired. Rather than being released back into the wild, Journey was given a new purpose: an educational ambassador.

Beginning in 2003, Phyllis and Journey traveled to schools, libraries, nursing homes, and public events to teach people about the magnificent great horned owl. Phyllis named him Journey because it became his life’s journey to teach humans about his species.

“It became his life’s journey to teach humans about his species.”

What Journey taught me—and what I included in the book

Besides telling Journey’s story in narrative form, I included a section of facts so readers could learn more about the great horned owl. I like books that combine story with learning; it’s especially helpful for children who are curious about animals.

Selected facts about the great horned owl

- Not pets: Owls are wild animals; it is illegal to keep them as pets. Wildlife rehabilitators must have special permits to care for them.

- Size and shape: Great horned owls have a barrel-shaped body and weigh roughly 3–6 pounds.

- Vision: Their large eyes let in much more light than human eyes do. Owls see primarily in shades of black, white, and gray because they have many light-sensitive rods. They see far better than we do in dim light.

- Head movement: Owls cannot move their eyes in the sockets; they turn their whole head instead. They can rotate about 270 degrees—not a full circle.

- Ears and ear tufts: An owl’s ears are small slits on the side of the head and are asymmetrical to help locate prey by sound. The “ear tufts” you see are just feathers used for camouflage; they’re not ears.

- Facial disc: The concave facial disc funnels sound to the ears; with this amazing hearing, an owl can detect a mouse a half-mile away, even under snow.

- Silent flight: Their wing feathers have serrated leading edges that muffle sound, allowing silent flight and slow-speed maneuvering.

- Feet and talons: Feet are feathered for insulation and end in extremely sharp talons for gripping prey.

- Diet and pellets: Mostly small rodents, but also rabbits, birds, and sometimes skunks (owls have a limited sense of smell). They regurgitate fur-and-bone pellets which you can often find below a roosting tree.

- Life span: Wild great horned owls average around 18 years, though Journey has lived considerably longer in human care.

Educational outreach: bringing Journey to people

Journey’s role as an educational ambassador meant he attended talks at libraries, schools, and nursing homes. In one memorable visit to the Crystal Falls Library, our small meeting room packed in 56 people—kids and adults—to see Journey up close. Despite the excitement, Journey was a nocturnal bird and often sleepy during daytime events. He trusted Phyllis, however, and that trust is what allowed him to serve as a living teacher.

Journey’s role as an educational ambassador meant he attended talks at libraries, schools, and nursing homes. In one memorable visit to the Crystal Falls Library, our small meeting room packed in 56 people—kids and adults—to see Journey up close. Despite the excitement, Journey was a nocturnal bird and often sleepy during daytime events. He trusted Phyllis, however, and that trust is what allowed him to serve as a living teacher.

When I visit classrooms, I often bring a hand puppet modeled after a great horned owl—about the size of the real bird—with a working head turn and blink. Kids love it, and it helps them learn without disturbing a live animal. For safety during demonstrations, wildlife handlers use thin leather straps called jesses attached to the owl’s legs and thick gloves to protect against talons.

Behind the scenes: writing, research, and illustrations

Research was one of the biggest parts of making this book. I had about a hundred pages of material to condense into a short, child-friendly story plus a factual section. Working with Phyllis was invaluable—she provided the details about permits, rehabilitation, and the daily care of Journey.

My process was fairly straightforward: I wrote the story first so I could decide what illustration would best accompany each page. Once the text was stable, I painted the watercolors (with some ink for finer lines). Watercolor is unforgiving—you can’t simply erase—so it requires planning and patience. After the artwork and text were done, I worked with my printer to edit and finalize the book for print.

Questions people often ask

- Could Journey ever fly again? No. The wing damage was too severe for a full recovery. When possible, wildlife rehabbers do try to heal animals for release, but Journey became an educational bird instead.

- Does being used in daytime programs harm a nocturnal owl? It can be tiring. These birds are nocturnal and naturally prefer the night. During daytime programs Journey often seemed groggy, so handlers work to minimize stress and keep programs short and predictable.

- Did Journey bond with Phyllis? Journey trusted Phyllis—trust is crucial. While he was still a wild animal, he came to rely on her as his caregiver and provider.

Where I go from here

I’m always working on something new. I have another book nearly finished and am waiting for feedback from other rehabilitators involved with that animal’s story. Winters are my painting season; summers I spend outdoors gathering inspiration. I’m never bored—there are always new subjects and stories waiting to be told.

A thank-you and a few practical notes

Thank you to UPPAA and the Crystal Falls District Community Library for hosting the UP Notable Book Club and for inviting me to speak. If you’re a writer or illustrator in the Upper Peninsula, consider getting involved with UPPAA. The UP Reader accepts stories (500–4,000 words) and submissions are open to members; the next deadline mentioned in the talk was November 10. UPPAA also hosts a conference—an excellent opportunity for writers at any stage—to connect and learn.

If you’d like to find a copy of The Story of Journey: The Great Horned Owl or learn more about my work, the book is available through common retailers and local outlets. I hope Journey’s story inspires young readers to appreciate owls, wildlife rehabilitators, and the wild places of the U.P.

Final thoughts

Stories like Journey’s remind us that wildlife and humans can form meaningful, educational relationships when handled responsibly. Whether through a page in a book, a watercolor painting, or a careful, permit-authorized program, sharing accurate, compassionate information about animals helps foster respect for the natural world.

— Carol L. Schultz