Why the snowmobile story matters

Larry Jorgensen

Snowmobiles are more than machines that move over snow. They are the product of stubborn inventors, quirky experiments, regional necessity, and a culture that turned winter from barrier into playground. The history is full of brilliant successes and spectacular failures, and it says a lot about human ingenuity: when faced with deep snow, people tried everything to make something go. In this episode, we feature author Larry Jorgensen providing tales from Make it Go in the Snow: People and Ideas in the History of Snowmobiles

From a hardware-store shed to a standardized machine

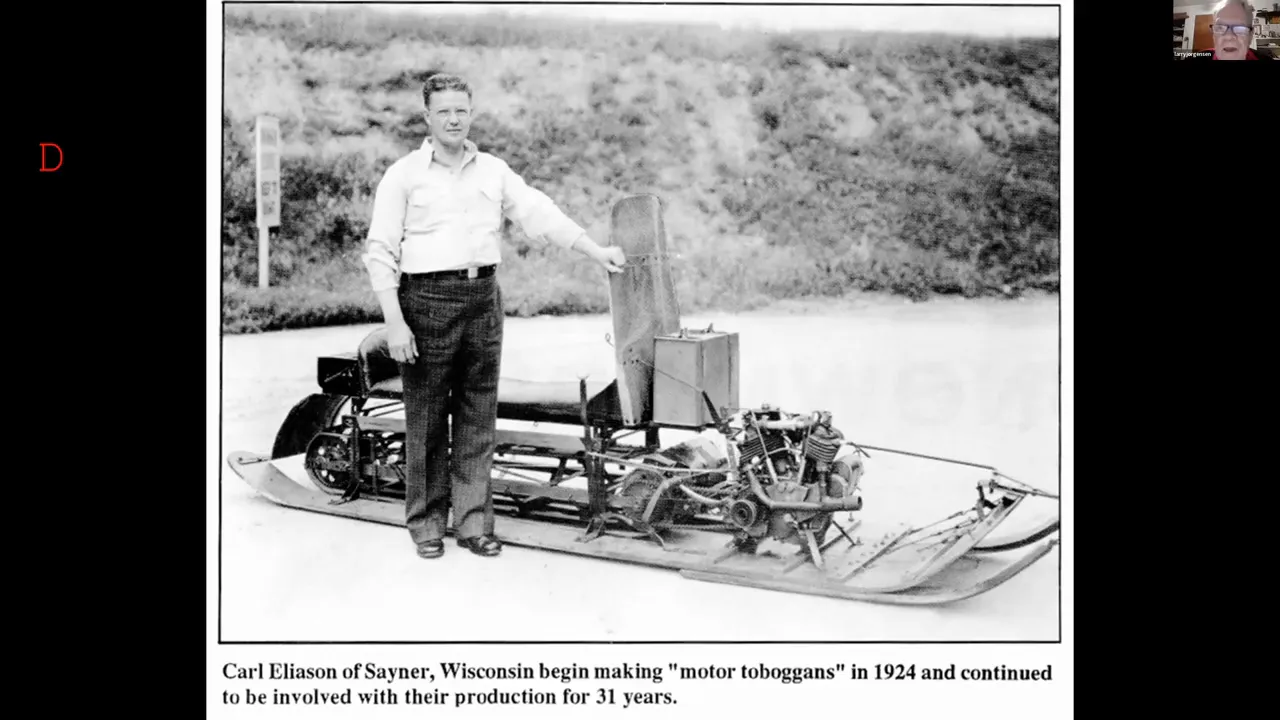

Carl Eliason is often credited with shaping what we recognize as the modern snowmobile: a vehicle that uses a moving track for traction. Eliason tinkered in a small Wisconsin hardware store for years, cannibalizing motorcycle engines and whatever he could find until one design finally worked.

His machines became popular quickly, but small-scale production couldn’t keep up. Manufacturing was licensed to a larger company, production moved, new brands arrived, and the original maker faded into history. Still, patches of that early work survive in local museums and the family hardware store that remains a quiet landmark in Eliason’s hometown.

Air power and the Snow Devil family of ideas

Before tracks became the norm, a surprising number of inventors tried propeller-driven machines. These air-powered sleds could be fast and loud, but they brought problems: poor braking, safety hazards from exposed props, and handling so aggressive it knocked limbs off trees.

One colorful example is the Snow Devil — an airplane engine and prop mounted on a sled. It worked well enough to haul supplies to remote resorts, but it required a passenger to act as both mechanic and improvised brake. Air-driven sleds left an impression, and later companies experimented with similar ideas. A few survive as restored curiosities at annual gatherings where owners race and celebrate the oddball legacy.

Joseph Bombardier and the lineage that led to modern makers

A teenager named Joseph Bombardier experimented with an air-powered snow vehicle using a salvaged Model T engine. That early curiosity grew into a company that would leave a global imprint on snow transportation. A reconstructed version of his first vehicle sits in the Bombardier museum as a reminder: many big names began as backyard experiments.

The name Snowmobile and early Model T conversions

The word “snowmobile” itself was copyrighted as early as 1917 for an attachment that converted a Model T into a snow-going vehicle. Henry Ford took notice and offered to let the inventor supply convertible units to Ford dealers. That era produced practical winter conversions and even saw one unit make the trip to polar exploration. Small farm implement companies converted to winter production and made several models until wartime pressures and resource shortages ended many of those lines.

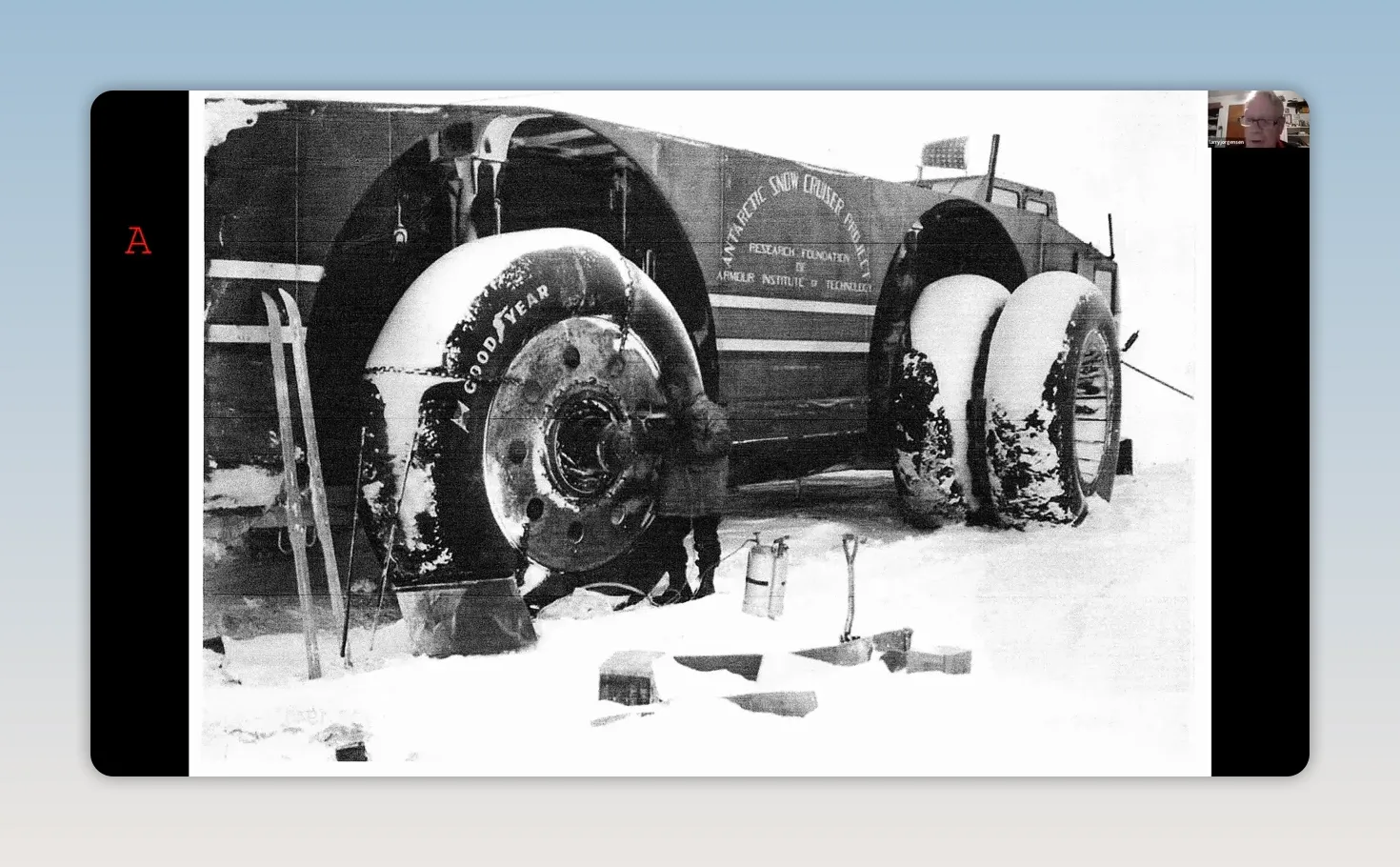

The giant Antarctic machine: bold ambition, limited results

One of the grandest attempts to “make it go” was a multi-ton vehicle built for Antarctic exploration. The idea was simple: make it so large it could not fall into crevasses and even carry an airplane. Built with help from established manufacturers, the vehicle made headlines as it lumbered through towns — taking up both lanes — but it failed spectacularly on the ice. Tires would not bite, the design could not adapt to shifting conditions, and the machine ended its days as a field shelter or, possibly, under the sea after the ice shifted.

Screw propulsion, Henry Ford, and the North

Screw-propelled vehicles look like rotating cylinders that “drill” through snow. Henry Ford backed experiments using Fordson tractors equipped with giant screws on both sides to traverse Arctic terrain. The plan included hauling aviation fuel to remote points for exploration flights. In practice, weight, terrain, and logistics made the convoy impractical for long Arctic runs. A few of these machines survive in museums, a testament to a bold but flawed idea.

Modern attempts and corporate missteps: Honda’s four tries

Not all big companies succeeded. Honda tried four different approaches to enter the consumer snowmobile market and failed each time — for reasons ranging from poor dealer fit to unfortunate safety incidents. Their attempts included:

- a heavy, four-cycle motorcycle-powered sled that dealers rejected

- the light, rear-engine “White Fox” with a push to select dealers; a serious accident in Canada prompted a recall and near destruction of remaining units

- a twin-track cockpit-style machine that stalled due to management disagreements with the manufacturing partner

- a motorcycle-to-track conversion marketed in Japan but too awkward for U.S. handling preferences

The “White Fox” is now a rare museum piece. Honda’s story shows how even massive engineering skills must align with user expectations, safety realities, and dealer support.

Trailblazers and grassroots adventurers: the Peninsula Pathfinders

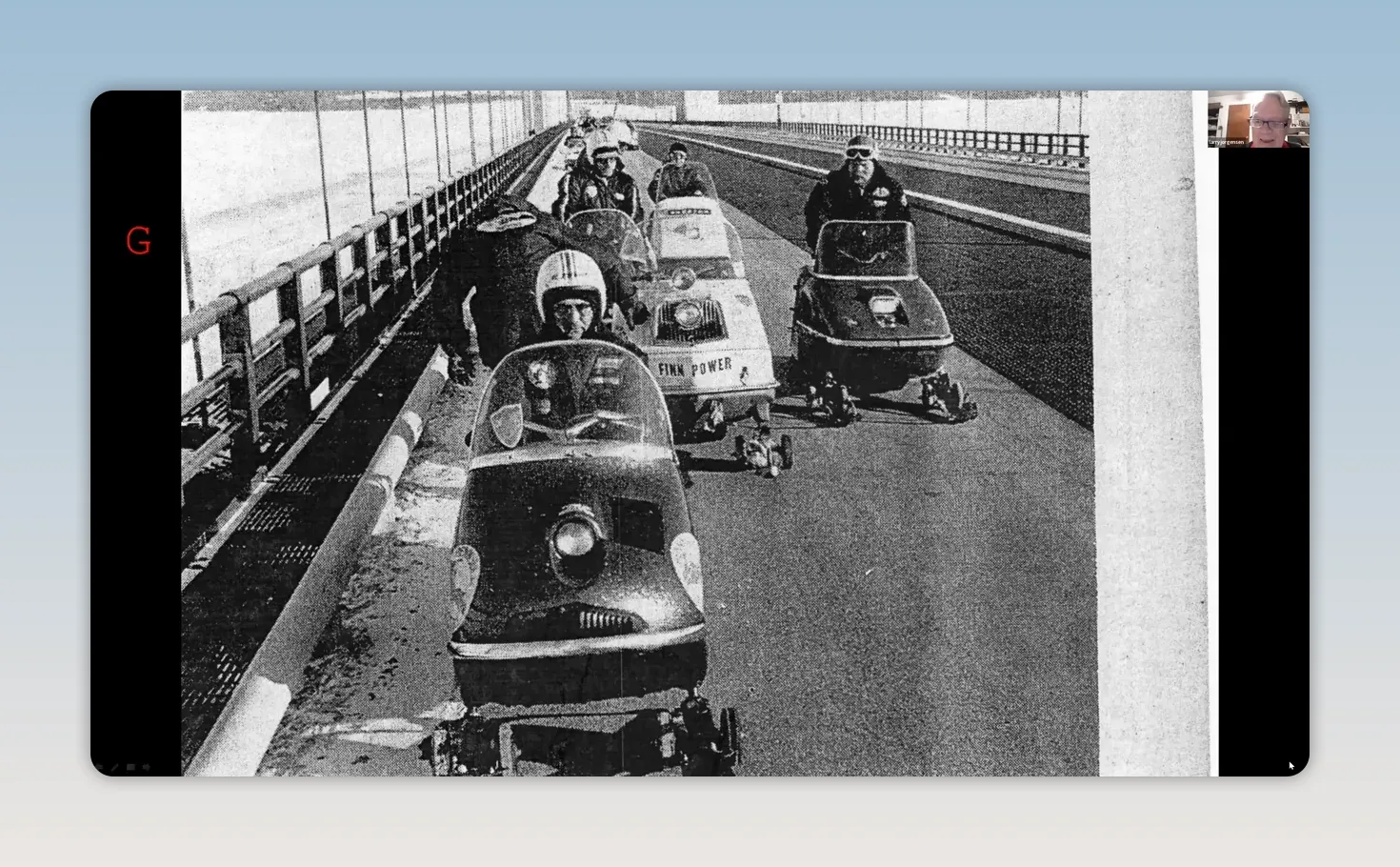

Clubs of riders did more than ride. Groups like the Peninsula Pathfinders from Marquette campaigned for cross-country trails and staged long-distance trips that proved snowmobiles could connect communities. Their trips read like an adventure diary: Copper Harbor to Green Bay, crossing the Mackinac Bridge on a cold spring morning, trips through Canada to the Atlantic shore, and even accidental tours of Finland when travel plans went off the map.

Those trips built trail culture, fostered safety standards, and gave rise to the modern sense of community that surrounds snowmobiling today.

Racing, stunt engineering, and the limits of experimentation

Racing, stunt engineering, and the limits of experimentation

Racing pushed the machines and the rules. The Snow Pony story is a classic: a tiny sled converted from a dragster that used a jet engine for exhibitions and then set a land speed record in an experimental class. Other racing experiments saw twin-engine setups using go-kart motors, machines that required starting two engines at once, and handlebars smoldering under extreme conditions. Racing proved exhilarating but dangerous, and it brought both notoriety and practical advances.

Museums, preservation, and where to see the machines

Many of these stories are best experienced in person. A handful of museums preserve early Eliason models, reconstructed Bombardier machines, rare Honda White Fox units, and eccentric screw-propelled tractors. For anyone curious about the evolution of snow transport, visiting regional museums — especially the large vintage snowmobile museum in Nabinway — delivers context, history, and a surprising collection of oddball machines.

What these experiments teach us

The history of snowmobiles is a study in iteration. Inventors tried the obvious, the exotic, and the improvised: tracks, props, screws, twin engines, and more. Success usually followed a design that balanced traction, simplicity, safety, and dealer support. Failure often followed when one of those elements was ignored.

Enthusiasm and regional needs drove most advances. In places where snow was a barrier to life and business, people did not have the luxury of waiting for perfect technology. They improvised. That spirit turned winter into possibility.

FAQ

Who invented the first practical snowmobile?

Carl Eliason is credited with creating the first practical track-powered snowmobile. He developed machines in northern Wisconsin that used moving tracks for traction and eventually licensed production to larger companies.

Did anyone try air-powered snow vehicles?

Yes. Early experiments used airplane engines and propellers mounted on sleds. Examples include the Snow Devil and earlier designs by inventors like Joseph Bombardier. Air sleds could be fast but had major safety and handling problems.

What was the White Fox and why is it rare?

The White Fox was one of Honda’s lightweight, rear-engine snowmobiles produced in limited runs and issued to select dealers. After a serious accident and a company recall, most units were destroyed. A handful survive in museums and private collections.

Were there giant snow vehicles built for Antarctica?

Yes. A massive vehicle built for Antarctic exploration aimed to avoid crevasses and even carry an airplane. In practice, it failed to perform on polar ice and served briefly as a shelter before disappearing as the ice shifted.

Where can I see early or rare snowmobiles?

Several regional museums preserve early models, including reconstructed Bombardier machines and rare Honda units. The Vintage Snowmobile Museum at Naubinway is one of the most extensive collections in the country.

How did clubs like the Peninsula Pathfinders influence snowmobiling?

Clubs organized long-distance rides, advocated for cross-country trail systems, promoted safety, and helped build the social culture of snowmobiling. Their adventurous rides demonstrated the utility of snowmobiles for connecting remote communities.

Further reading and next steps

For an in-depth tour through these stories and many more oddball experiments, historic photos, and local anecdotes, look for histories of snowmobiles that collect inventor biographies, company histories, and club chronicles. Museums and local historical societies often provide the most vivid artifacts and backstories.